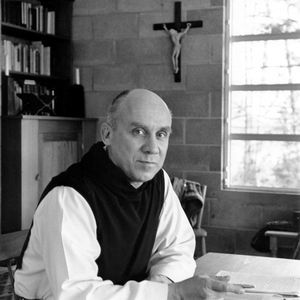

These comments from Thomas Merton, which I owe to Prof. Gregory Hillis, match my own feelings. That someone will comment unfavourably on Merton, and that they will do it from the conservative position Merton describes, is inevitable- and prove Merton’s point. Too much of the reaction to Amoris Laetitia shows a closedness to each other. From the liberals I so expect it that, sadly, it ceases to even worry me. Their desire to turn the Church into a creature of their imaginings is so strong that they fail even to grasp the poverty of their imagination. That so many conservatives seem to match Merton’s description does worry me because, on the whole they are on the right side of things. What custom and practice have sanctified we should be slow to want to change, and what is doctrine and dogma cannot be changed. But how sad it is that some here cannot see that it is out of argument and discussion that so much of our dogma and doctrine have developed.

When Arius began to explain to us why the New Testament supported his argument that Christ was a creature, he crystallised a line of thinking which had a long pedigree, and in so doing provoked others to explain why he was wrong. But even the decision of the Fathers at Nicaea that he was wrong, failed to settle the argument. This was not because the Church was full of heretics, it was because Arius’ line of argument spoke to simple minds who could grasp that if God created every thing and he had a son, he must have created the son too. That was far more comprehensible than the idea of God being uncreated and the Son being uncreated, and the Son and the Spirit proceeding from the Father. Had Athanasius and others not kept the argument going, we should not have arrived at the agreement we did on the Trinity and the Creed. Had he and the Arians been capable of discussing this without throwing anathemata about and using force, who knows, it might even have been settled in a better way, but the point stands – discussion, even heated discussion, is better than suppression and no discussion.

It is sometimes objected that all of this is too much for the general public – as though somehow the search for greater understanding of the Truth is some gnostic enterprise to be carried on in private between consenting adults. It was not so in the time of Athanasius, and cannot be so in a world of mass literacy. Catholics have always interpreted the inessentials, and sometimes the essentials, in different ways, and the Church, unlike some of those who claim to be it or to speak on its behalf, has encompassed a wide variety of styles of worship and even interpretation. Those who are of a decided opinion can find this process uncomfortable, but it is inevitable – unless one wants to proceed as we used to on a basis of banned books and an absence of free speech. As the Merton quotation shows, there are those, on all sides who, it seems would feel happier with this. They cannot it seems to me, call Christ in aid of that – which is why his church proceeds the way it does.

It is out of discussion and debate that deeper understandings of the truth have emerged – even, sometimes, by ways no one could have expected. We either have faith that the Church is what it claims – in which case it cannot lose the Truth – or we don’t, in which case why are we in it?

You close another viewpoint before the critique is even made. Merton was is a difficult personality to get one’s arms about.

http://www.catholic.com/magazine/articles/can-you-trust-thomas-merton

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think there is a point where Merton begins to become dangerous, this is, of course, when begins to blend Catholicism with the East. However, Merton does provide exceptional writings when first converts to Catholicism and writes “Seven Storey Mountain.” In fact, in the introduction, The Thomas Merton organization writes for the reader to be aware of that Merton converted to the Pre-Vatican II Church and with his zeal would be very Conservative.

It appears from this selection that was selected by C that he’s come down off of that high feeling. In this particular text, I would simply ask with Merton, “Do we detect any influence from Eastern religions?” So far from this selection, I do not see any.

LikeLiked by 2 people

If you read the article, you can see that he had a real problem with authority. He and his abbot did not get along and Merton had deep seated resentment for his own abbey. I choose to look to others as a guide as to how to be a good Catholic. He was man in turmoil and by the end had about chucked it all for Zen Buddhism.

LikeLike

I look elsewhere myself. In my opinion, I know the more conservative Catholics will probably disagree, but the last two Popes prior to Francis were exceptional writers and voices on the faith. Often when I have a question needing be answered, I first look to them.

It’s strange though because someone like JPII is despised by an old college professor of mine who claims to be Catholic. He posted a picture of the Canonization of St. John 23 and I replied let’s not forget the Polish Pope. The ole’ professor’s reply was, “his feast day won’t be on my Calendar.” Of course, the other day, Michigan Man utterly refuses to call Pope St. John Paul II a saint.

I think in a sense these are the two wings that C is attempting to discuss, which is why I find so much wisdom in the Polish Pope.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I very much like the writings of the previous 2 popes. So far, I am not at all impressed by the writings of the present Pope. Purely my subjective take away. They seem confused. He does not speak the yes, yes or no, no we are used to. He speaks in maybes, sometimes, perhaps etc. which just makes the fog all the more thick.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think we have to be also conscious that we have been spoiled by St. JP II and BXVI. They were exceptional academic minds.

LikeLiked by 2 people

We were indeed. We do tend to have high expectations because of it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been also thinking about writing a post a St. JP II’s first encyclical. As I view our current state in the world, it appears apparent that it’s a document that needs reexamining in the face of this new form of secular atheism in the United States.

However that idea will be on hold, I am still currently working on a post series on Moses.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That might be very interesting Philip. Posting it here or at your own site?

LikeLike

Moses will be on the site, I’ll send it to C when I’m done. It’s on the topic of the historicity of Exodus.

JPII will be my site.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’ll try to keep my eyes open for it then. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That would be excellent.

LikeLike

He would hardly be the first or last to have trouble with authority, but I don’t think the last part is true. He was a thinker who obsessed with whatever his subject of the time was and moved on to incorporate it into Catholic thinking. His sudden death cut the story short, and I don’t think we can speculate on where he’d have gone.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m not at all convinced that he wasn’t already there, C. Perhaps you are. Seems he veered off the tracks in my opinion and kept looking for another pearl after he already found the pearl of great price.

LikeLike

I would be interested in what your argument against what he says here is. It is a shame you went straight for the man and not the ball. Prof Hillis, whom I quote, knows more about Merton than most, and he is not at all convinced by the arguments that he was leaving Christianity behind. Interestingly, those come from the sort of conservative he was criticising here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My suspicion of Merton comes from years of reading and practicing Buddhism and entertaining their Eastern way of thinking. I found that it led to annihilation of self and an almost hypnotic ethereal dreamworld where nothing bothered you; a false peace if ever there was one. That is why I do not trust much of his judgement on matters . . . that he could still write orthodoxy is not a great feat. It is also not a great feat to come up with a caricature of right versus left within the Church that errupted after Vatican II. Is there a middleway of accepting both views or is one right and one wrong? Seems to me that we are in the midst of trying to sort that out at the moment. You have your mind made up as did Merton at the time. It is certain that time will eliminate the corrupting elements of the faith in time but there will be new ones to contend with as well; there always will be. I’m not sold that the traditional/conservatives don’t have the better arguments especially in view of the situation on the ground and in the pews. It is rather obvious that the RCC has lost what we used to call a Catholic Sense due to our Catholic Culture. Divorcing the expression and practice of faith from the teachings of faith has produced a world of problems to be sorted through. And this is just one more instance of this. Do I think that this document will be used in a way that will abuse Church teaching? Yes. Will it be general or will it only be relegated to a few dissenters who will do that? I don’t know. All I do know is that I am wary and weary after these last 25 years or so . . . as we were pretty sure that the past two popes had delivered much needed guidance in reigning in the change agents. Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me. Color me skeptical.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t see it is a caricature. It is terribly easy on the Internet and in real life to find Catholics who fit like a hand in a glove that description. The one thing we are none of us qualified to do is to impugn the Catholic faith of our fellow Catholics – and that both conservatives and liberals do it seems to me a scandal.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Does that include suspicion then? Are you not suspicious of de Chardin or Kung? As for the internet, I could find scores of people that fit any description that I might make to fit the times as well. It is almost limitless. But they are all entitled to be in this melee and be heard. I do try to limit my internet reading to those who actually believe in the Church teachings and practice however. The differing views from that perspective deserves more attention than the meanderings of bloggers like myself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

De Chardin, not at all suspicious. Kung’s licence to teach as a Catholic was withdrawn, and rightly, but much of what he writes can be read with profit.

I can’t adequately convey the depth of my commitment to freedom of speech and thought. If people don’t like x or y, fine, but they should be free to write and speak. But then, having myself, experience of people trying to silence me, it runs deep and gets personal 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I understand that. But I can’t adequately convey the depth of my commitment for the Church to guard her sheep from the wolves and to give them bread rather than a scorpion or a stone.

Maybe I should have used Anthony de Mello as one of the ones I’m suspicious of . . . would that have raised an eyebrow as well?

LikeLiked by 1 person

We have bishops and Cardinals for that – we should surely not presume that we, as laymen, are better equipped than they are?

LikeLiked by 1 person

And we should not presume as laymen that they are all speaking with the same voice. They are as different as night and day on many issues confronting us presently. Should we ignore that and just pick the one that feels comfortable to walk in?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Isn’t that what you are doing? Or am I misunderstanding?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Probably so. Are you? Or are we each doing the best we can with what intelligence and learning God gave us? This should not be subjective but it has become so. Why? Because once the Church did protect us. Once an imprimatur and a nihil obstat meant something and every Catholic writer sought such. Once, dissenting theology was not presented to the laity. It is Vatican II that threw us out to pasture in the world with the wolves to fend for ouselves; having widened the role of the laity. We now suffer from the ‘broadmindedness’ that Bishop Sheen warned us against. I don’t think this is what Newman had in mind by entertaining all views but I might be wrong. We are either closed minded on some things (that we subjectively choose) and broadminded on others (which we also subjectively choose) or we just become indifferent altogether. Making up ones mind was at one time a good thing and broadmindedness a sign of weak faith. I think we have an increase of weakness in faith these days. If we’re waithing for some white knight to emerge and bring the bishops, priests and laity together I think we are being a bit over optimistic.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t think I am. I am as happy to read Kasper as Sarah and don’t think one less Catholic than the other. I am as happy to read Aquinas as de Chardin and de Lubac – and by that I mean read their books not what those who wish to denounce them as heretics say their books say.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And I am not happy to have the word Catholic applied to authors that confuse or contradict Catholic teaching. There are far too many uncontroversial Catholic authors to read which would be had to get through in a lifetime. If you are in the position within the hierarchy to consider their ideas and pass judgement then it makes sense to read them. If not, my choice is steer quite clear of that which isn’t clear.

LikeLiked by 3 people

No one is forced to read anything. De Lubac and de Chardin are both Catholics and I would be interested to know why anyone with the authority to do so would deny them that title.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And because one is Catholic they don’t err? We have not seen as many condemnations as we did in the past but that is not to say that they have straightened out their theology. It may be that they are simply over run with such things and can no longer cope with the enormity of the task.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I don’t see how it is possible to write and for someone not to think you have erred. There are many things on which the church has not pronounced definitively of course.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Those aren’t errors as you well know and not what I am speaking of quite obviously. But in the case of getting an imprimatur and nihil obstat presumably the book is free of error not free of speculation where speculation is OK.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The system broke down because it could not cope with the number of books being published in the 60s – can’t see it would work now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We don’t have a choice here on freedom of thought. We could behave as much like Muslim extremists as we liked, and we’s be viewed the same way. The Truth has nothing to fear. Suppressing books did not work, except against us. We became intellectually flabby and lazy and when we finally had to face the real world which we could neither ban nor suppress, we lacked thinkers who could do it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That may be true if that were the case among the hierarchy whose job it was to entertain all advances in theological thought. But you seem to think that the laity (the sheep who are to be led) are to be exposed to as many wolves as possible; even to their being devoured. I am not of such a mind nor do I think Newman was speaking of them.

LikeLiked by 2 people

In the age of the Internet quite how you are going to ensure people only read approved books I can’t imagine. The real problem seems to me to be so few ever read any books at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When priests are pushing these things in adult education classes rather than education in the Catechism which the sheep actually need, it is a concern. They expound on questionable writers at the pulpit and we wonder why they can get away with this.

LikeLiked by 2 people

But how often do we wonder whether our bishops might see things we don’t? How often do we winder if we’re wrong?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Some do and some don’t. We had a bishop for a while that sent out people to sit in the pews in civilan attire to evaluate Masses and such. But he was the only one that I am aware of that did this. Not all bishops are equal and we all know that. If we have access to a catechism of the church we might not wonder too much about whether we are right or wrong. If not enforced by teaching and practice then it serves no purpose at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Let me give you an example of how they are taking care of us. We had a priest in Columbia that taught RCIA from the book Christ Among Us by Anthony Wilhelm. The book was banned by the USCCB for use because of heretical sections in the book. The bishops are not watching what is being done or sometime between 1967 and 2005 somebody would have noticed this. So the question is this. If the bishops and their priests are not protecting their flocks who must step up to do so? Or do we have to fend off the wolves ourselves. I’m not one to let myself get devoured and if I need to fight the wolves to my death I will do so. I’m happy that there are others there that will fight at my side. As for the hirelings who are hiding under their desks and pontificating, I find no aid or comfort in their noticable absense from the fight.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Easy enough, surely, to point that out to the Bishop?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Do you really want a list of horror stories about laity bringing irregularities to the attention of their bishops? I’ve been privy to a good number of them personally and read many more. I think you probably have had the same experience in the UK or is jus the US that has gone quite mad? 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are other avenues when that one fails. Sometimes we seem very sure that others are acting in bad faith – and yet get upset when they assume we are. Perhaps none of us is?

LikeLiked by 1 person

It doesn’t stop the problem of propogating lies about the faith. Yes, there are means by Canon Law to take the fight up the ladder. But is it up to the laity to have to recognize these things, fight with great anxiety the powers of the Church to just get beaten down? Surely, things worked better in the past than they do at present.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Some things did. But I don’t think banning books a good idea – and, of course it didn’t work. We can’t go back to the past.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Imprimaturs and nihil obstats were a good thing. We didn’t need a ban on books as much as we need an authority to guarantee that a writing will not be harmful to our faith. Do we not need this as much as a parent needs this in regards to ratings for a movie?

LikeLiked by 2 people

At the pace the Church moves nothing would get published. That’s one reason the practice was abandoned in most cases. Can you imagine how it would work given the number of books that get published?

LikeLiked by 1 person

They kept up with it in the past pretty well. Seems it could have grown right along with the number of would be Catholic authors.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My information suggests that by the 60s there was a five year delay – I can’t see that would be less now. It isn’t as though you can’t find opinions galore on the Internet. I don’t know who is reading all these books!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perhaps people interested in becoming Catholic and discovering things in our theology that aren’t really in our theology. Somebody is buying the books or they wouldn’t be published. As far as the five year delay, then the bishops should have put more resources at the disposal of this endeavor. If the movie industry can take care of it then the Catholic Church should be able to cope with this as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And would these all go to Rome, or local bishops of the sort you distrust? I doubt it would justify the huge expense.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And there is the rub. A lack of leadership allowed us to have dissenting bishops and no one is right and no one is wrong. None get their hands slapped much less excommunicated though we all could hand in a list of one’s we know would have been in the past.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Isn’t that falling into the very trap Merton describes?

LikeLiked by 1 person

The trap of actually having to believe and teach the Catechism of the Catholic faith . . . to actually do the red and read the black? So be it, if you call that a trap.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Theology is not a matter to be reduced to such a simple division. Merton’s point is that some liberals forget that the church has a tradtion, whilst some conservatives forget it is one that develops.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A development or a blossoming is not even questioned; further insights into a preexistent teaching. But if the ‘insight’ contradicts or weakens the teaching then is it a development? That is the question that needs be answered in my mind. The same with the estrangement of practice to dogma. When is it counterproductive? When has it been productive?

People once had a Catholic sense about orthodoxy and that is why so many were scandalized by what they saw come out of the VII council; mostly what many priests and bishops presented to them . . . clown masses and a burning of the old Baltimore Catechisms etc. But we are now at a point where we are desensitized to orthodoxy. The sense of orthodoxy is almost extinguished.

In my own parish we went from orthodoxy to unorthodoxy and the bobbing heads nodded approval to the teachings of both; though both were almost at the other end of the spectrum concerning the Catechism. So I doubt that is a good outcome.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, sometimes, as with Arius, it can lead to sharpening orthodox focus. There never was a golden age 😄

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very true.

I was getting used to papal documents and verbal teaching which threw more light on a subject and cleared away some of the fog. Now I’m witnessing a return of the fog. It is not hard to see why this document is met with a wide array of opinion. I think it is inevitable. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

I am not sure ‘feed my flock’ is a model of lucid prose.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Church has made it so on several different levels. I wish it would do as much on the issues confronting us today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

When it tried to with Laudato Sii so many asked what the environment had to do with the Church – as thought God did not make the earth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not exactly. We know that God made the earth and that we are its stewards and that God holds it in existence until He no longer wills to hold it in existence. But the science itself was questionable. And I still do not understand how things like air conditioning is bad for man. We used to lose thousands of lives every year from heatstroke before air conditioning. Now even the poor in this country have access to air conditioning. It saves lives and it produces jobs. The harm to the planet is negligible compared to the natural sequence of events involving the sun, volcanoes and the like.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I am not a scientist, but I know many, and know none who do not think that we have done severe damage to or planet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have you Googled those who don’t? There are some pretty heavy hitters on that list as well. Then you can Google all the coverups of data that disproves the supposed ‘consensus’ which has become so politically or should I say scientifically correct that they refuse to publish their findings. It is astounding that the ‘open’ debate scenario is closed off by a bunch of elites that are driving this issue.

LikeLike

BTW: your professor friend called it a caricature himself: “In Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, Merton expresses his frustration with the intransigence of progressives and conservatives, and particularly their unwillingness to have their engagement with the other marked by charity. Merton’s focus is on ‘extreme’ conservatives and progressives, and so he does, admittedly, indulge in some caricature of each side.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

As in all caricatures he takes recognisable features and exaggerate slightly to make the point.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree. I thought you might chuckle at that though. I was actually looking for the date of publication that this assessment was made. As I found out it was 1966 and may well be a much better assessment for that time than it is for our own. The call that I see from the conservative side is for us all to stand together as Catholics. But in 1966 the talk was about schism and being railroded during the Council. So it might fit some today for sure but I’ll bet it fit many more churchmen then than it does now. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

I don’t, and I think we have to be careful. Merton was an eclectic thinker and died suddenly. We can have no idea of where his thinking would have gone, and should beware of those who say that he’d have ended up a Buddhist.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I wouldn’t say your statement isn’t true per say. However, in the stage of my life and in my faith, I do find his later writings concerning, which is why I would recommend any to read Seven Storey Mountain–especially those who have lost their faith– but my recommendations do stop there.

LikeLiked by 3 people

The thing is that we have here an incompleteness caused by his early and sudden death. It was interesting to see the man being played but not the ball. I remain unclear of the argument against what he says here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have no argument from what he says here in the context of the discussion. In fact, I would agree.

I am just speaking in regards to the writings that were written near his untimely death. We can speculate that he would have clarified himself much like Augustine did near the end of his like in his Retractions, but Servus could be right as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It could be, and we can’t know, alas – but yes, the comparison with Augustine is a good one. Had he died ten years earlier than he did it would be interesting to speculate as to whether he would have the influence he came to have.

LikeLiked by 1 person

He is, but what he says here seems to me on the money.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well there are many viewpoints on the conservative/progressive divide as well. That it agrees with you, is obvious. There is much that I largely agree with as well but I am open to other models that explain the divide.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me too 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well said, both you and Merton. And now, I fear, the deluge!

LikeLiked by 1 person

As you should, seeing as though C has made up his mind before the argument is made and will not even entertain another viewpoint if it is not his own. As to the idea that the Church has lost the truth, no argument has been made that I have read yet that this is even being said. What is being said is that the practicice is being separated from teaching.

LikeLiked by 1 person

But Servus? Can the Church have truly lost the truth? Wouldn’t this be in conflict with Christ’s prophecy that the gates of hell would never prevail?

LikeLiked by 3 people

Did anyone say that the Church lost the truth, Philip. I think I said exactly the opposite. Best read again.

LikeLiked by 2 people

My apologies, I did read it wrong, which is why I questioned it. I thought, oh my, what has happened to you! 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I thought that was the case. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well enough on Merton or de Chardin or whoever else we might want to drag into the fray. What do you think of this interesting bit from a new priest’s comparison with Brideshead Revisited. I thought it was a different way of looking at things and worth pondering.

http://rorate-caeli.blogspot.com/2016/04/guest-op-ed-pope-francis-pro-mundum.html

LikeLike

I thoroughly enjoy Brideshead! Let me take a look.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It’s an interesting analysis of the Novel in context of the Pope’s document. However, I’m confused in the aspect of how Francis has contradicted the revelations made by Julia and Charles. It would appear that they both discovered a relationship with God, isn’t the Pope addressing this in his document? Does the document actually say that divorced Catholics can have communion? Isn’t that some already formed biased being read into the document? It seems to be the opinion of Cardinal Burke that the document doesn’t express a change in doctrine.

The media and the two extremes of the faith have interpreted the document which more or less promotes their agendas rather than God’s. Isn’t that at the heart of the lesson of Brideshead?

LikeLiked by 2 people

i thought he explained it well or maybe thats just me. My take would be summed up as ‘meeting people where they are’ is being turned into ‘leaving people where they are.’ Cardinal Burke is right; teaching has not changed. We all knew that already. That it is up to the priest or the individual bishops to allow these people to violate law has certainly been opened. And once you leave the barn door open we all know what we can expect. Just sayin . . . keep your eyes opened wide to see how the various bishops and priests of the world incorporate this or reject this advice. Reminds one of the liberties many priests and bishops took with the Novus Ordo . . . which morphed into most expressions of this Rite which was never promulgated from Rome. It is a mixture of what was promulgated and what developed by way of experiments that were made by those who tried every novelty in the book out for size.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I gained a new perspective over the weekend on the NO, I’m glad you mentioned it. From what I’ve read, my parish, for the most part follows the mass accordingly without liturgical abuse– at least none that is obvious.

However, I went to my nephews first communion and the Priest there seemed to make it up as he went… He didn’t genuflect at times and then did so at weird parts of the Eucharistic ministry. Not to mention, somehow during the homily he confused the explanation of the Eucharist with fish! My brother said, “well the Priest said…” I said, “the priest is wrong… ” He bewildered that I made such a statement, but it needed to be called out for the circus that it was.

LikeLiked by 3 people

That is the problem I am referring to which could be characterized by a Rite without consistent rules. The parish priest does whatever he wants and with all the options written into the Mass he could say it approximately 2500 different ways . . . I did the math once but forgot the exact number. That is what we call Mass confusion.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Servus,

I have been further reflecting on the matter of Brideshead. One of the problems that I have with the liberal view of the Church is that they have no purpose for suffering. In the grand scheme of Brideshead almost all of the characters experience suffering in their life in some nature, which in turn, did lead them to God.

We’re assuming that the Holy Spirit and God’s grace can no longer do its job in the modern world when we attempt to remove what makes is explicitly human nature. We must not play God, in fact, that’s what got us in the mess in the first place.

LikeLiked by 3 people

True Philip. We cannot leave people where they are . . . we must find a way to give them a goal to achieve and to make even an insignificant movement to meet God at some point. That is all that is asked really. Heroic faith may be for the few saints but the use of suffering caused by our disordered lives can certainly win the race to heaven if we just make a small effort. It won’t necessarily end the suffering but it will be repaid in grace which far excedes our percieved loss.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The question remans, how far is too far, when not only Brideshead has no purpose, but Isaiah 53 and Psalm 22 have none as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

True . . . but we hardly think like that anymore I’m sad to say.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The thing we must remember is that the Church Herself helped develop this loathing for giving up something. We removed the meatless Fridays for a penitence of our own choosing. Does anyone any longer give up anything even of their own choice on Fridays of the year? It seems we used teach that Catholics were a penitent people and now we have become too sensitive for any penitence whatever.

LikeLike

Interesting – but then Waugh was a novelist and not a theologian

LikeLiked by 1 person

He understood the Catholc Culture, quite obviously. And this priest understands that the outcome might be quite different in the future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Quite so, but of course, every individual circumstance is different, and if one took some of Greene’s novels I wonder what a similar analysis would reveal?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Never read Graham Greene as he was not that popular here (or at least in my literature classes at the university). So I can’t comment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Doing what is done there with Greene would be an interesting exercise I suspect.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If you say so; for I have no idea of what this even means.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Waugh is painting pretty black and white characters here – Greene has many shades of grey and offers more difficult moral choices.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It still does nothing to dispel the point that this young priest is putting forward does it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

No, but it is an easy one to make a simple point from – AL is most use when it comes to complex cases.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope that is the case. I think, like with many other things, it will be abused straight off. The Kaspers and the Germans have all they need to go their own way without anything to reign them in. They would have anyway but now they have the use of a document to make their life even easier.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Everyone will abuse it in their own way, they always do. There is nothing in AL which contradicts doctrine.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s all well and good only a wider breach has been laid between teaching and practice. It seems to be a theme that is advancing on every teaching we have. It is no wonder that we no more have a culture that is recognizable.

LikeLiked by 3 people

That’s one view. It might also be the case that we need a wider variety of practice to deal with our complex society.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We do if we want to be just like them. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think each of Waugh’s characters together have a complexity. I believe his point of making each character so blatant is so they the reader can examine those different characters that live in us. This idea is why the Priest can reference the novel.

LikeLike

I’ve never read Greene either, would you recommend a title that would compare and contrast well with Brideshead?

LikeLike

Indeed Arius had a fairly good Scriptural argument that the most literal, the simplest, interpretation of the text supported his view.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Should give us pause in how we read Scripture in what is popularly called the plain sense reading of Scripture, a very difficult problem in biblical hermeneutics as to what this constitutes anyway.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very good point – our friend Bosco provides excellent examples of the problem on a daily basis here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You rang

LikeLiked by 1 person

You appeared.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Quite so – that is, I am sure, why the heresy proved so persistent!

LikeLiked by 1 person

deeper understandings of the truth

LikeLike

Indeed they are not, and he was, as so often, right, but he did not shy away fro debates with Jews, atheists and agnostics. He was also suitably cautious about using the word ‘heretic’ – and unlike most of us, he was more than qualified to spot heresy. If we followed his example, we’d do better.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It is wisdom to be cautious to use the word heretic. If one uses it so much that it becomes an important part of their vocabulary , the word loses its true meaning and power.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s one possible explanation- another is some of us fit Merton’s description too close for comfort

LikeLike

Indeed. But Merton makes an excellent point.

LikeLike

Francis is unreadably prolix. What I can decipher is sophomore-level warmed-over hippie stuff. JPII was a phenomenologist but could at least be read. It has to be a trick of the devil that everyone has to signal that they are good warm-hearted merciful Catholics by saying they “enjoy” Francis.

LikeLike

Or, it could just be that others have a different opinion. No one would call Pascendi Dominici Gregis concise, yet it repays the effort needed to read it. I wonder how many have made the effort with AL. As a University teacher I’d be delighted to find a sophomore who could put that much effort into a piece of work. It is not, of course, written by Francis alone. Do reread the Merton quotation which heads up this post – the comment stream seems to me to bear witness to it – and the remarkable ability of some Catholics not to see it.

LikeLike